Drilling activity is gaining momentum, but will water scarcity constrain growth?

With oil prices stabilizing in response to recent OPEC production cuts, drilling activity in the US is again on the rise. As competition heats up in the most prolific production areas in the US, investors are trying to determine which companies will separate themselves from the pack. But water scarcity may prove more of a hindrance during this oil commodity cycle upswing than many expect, and companies dependent on growth in water-stressed regions may find themselves unable to deliver promised growth to investors.

How Much Water Is Too Much?

Much of the growth in US production in the past decade has been due to two technological advancements in drilling and completion technology: directional drilling and hydraulic fracturing. Simply put, directional drilling allows drillers a high degree of control of their well trajectory to hit the most prolific regions of the reservoir, making formerly prohibitive reservoirs more cost-effective to produce. Hydraulic fracturing is a process whereby a mixture of water, sand (aka “proppant”), and chemicals are then injected into the well at high pressure, causing small “fractures” to be induced in the reservoir. These factures are then “propped” open by the sand (hence the term “proppant”) to allow hydrocarbons to flow from the reservoir to the well bore. The combination of these advances have revolutionized domestic production in the US, leading to a near doubling in oil production from 5.2 million barrels/day in 2005 to 9.4 million barrels/day in 2015, and growth in natural gas production from 19.5 trillion cubic feet in 2005 to 29 trillion cubic feet in 2015, according to data from the Energy Administration of America.

The amount of water used in hydraulic fracturing activities depends on many different variables, including differences in the properties of the reservoir, the design of the well, and other factors. According to data from the United States Geological Survey, an average well drilled in the Marcellus Shale in Pennsylvania consumed 4.5 million gallons of water in 2012, while an average well in the Bakken Formation in North Dakota consumed 1.5 million gallons in 2012. For comparison, the average American family uses approximately 400 gallons of water per day according to data from the US Environmental Protection Agency. Thus, the water used for hydraulically fracturing one well in the Marcellus region could provide sufficient water for 30 families of four for one year.

Compared to other industrial users of fresh water, the amount used for hydraulic fracturing is quite small. According to data from the USGS, the average volume of water used for irrigation in the United States was 115 billion gallons/day in 2010. For comparison, of the 7,200 wells drilled in major shale-producing regions in 2016, operating under the generous assumption that each well consumed 4.5 million gallons of water, we can conclude that 90 million gallons of water was consumed per day (less than 0.1% of daily use for irrigation).

Thus, the absolute water usage is relatively small – however, this fact is often misleadingly referenced to suggest that access to water is not a significant risk for producers dependent on hydraulic fracturing. While true on an aggregate scale, investors should consider a key nuance with respect to water usage – specifically, water withdrawals from high water risk areas.

Water Risk – Hiding in Plain Sight

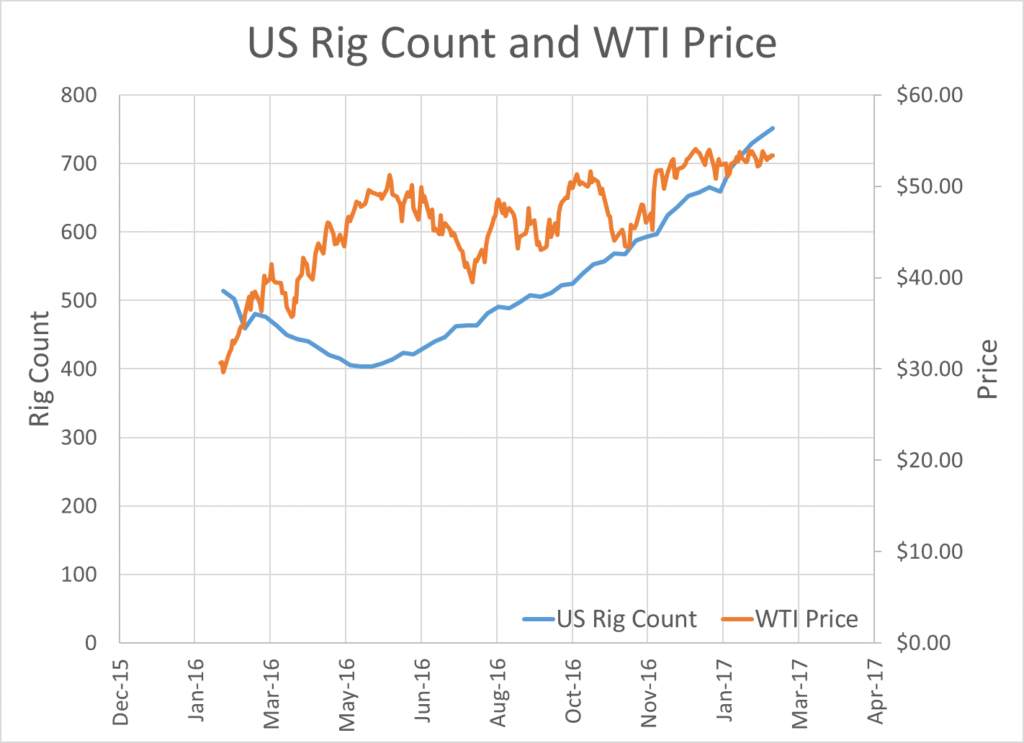

As noted in the introductory paragraph, drilling activity in the US has been on the rise. After bottoming out in late May of 2016, the US rig count has been growing steadily throughout the second half the 2016 and the start of 2017, according to data from Baker Hughes.

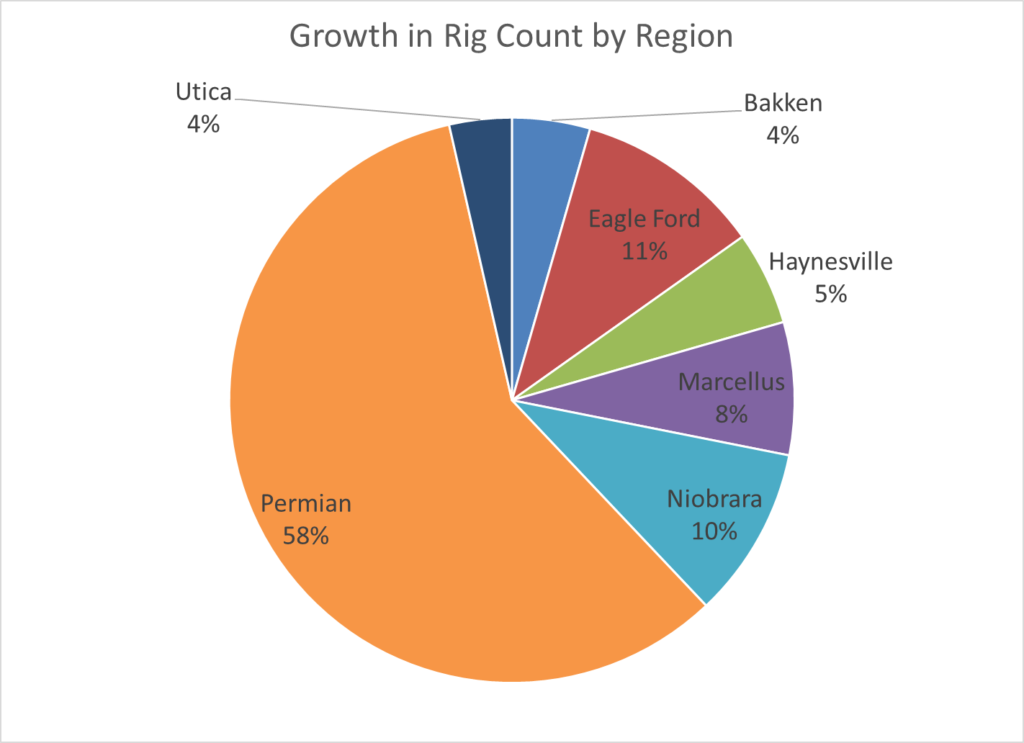

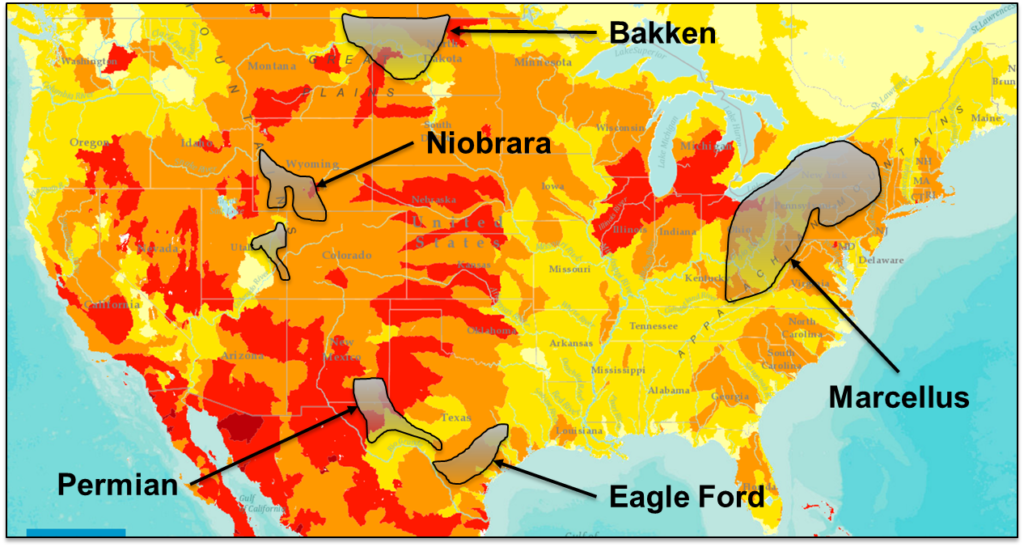

Most of this growth has been concentrated in certain geographical regions in the United States, including the Permian and Eagle Ford regions in Texas, the Marcellus region in Pennsylvania and West Virginia, and the Niobrara region in Colorado and Wyoming.

Due to the highly regionalized nature of the current growth in drilling activity, localised risk factors have the potential to have outsize effects on companies with relatively large exposure to these regions. Using the World Resources Institute Aqueduct tool, one can pinpoint localised risks associated with water stress.

Per the map above, the level of water stress varies significantly across the major shale production regions in the US. While the Permian region is characterised by high and very high levels of water stress, the Marcellus region is comparatively low-risk. Certain parts of the Bakken region are also characterised by high water stress. Both areas may therefore present localised risks to operators with exploratory rights concentrated in these regions.

SASB Helps Investors Quantify Sustainability Risk

Significant growth in domestic oil and gas production is projected to occur in the Permian region – one of the highest-risk areas in the United States with respect to water withdrawals. While total water usage for hydraulic fracturing is relatively low, localised use in water-stressed areas may present a significant, material risk for investors in companies that have committed to these regions for a significant amount of their growth. Supporting this conclusion, the EPA specifically cited localised water risk as a key factor in its comprehensive report on the impacts of hydraulic fracturing on water resources.

To account for this risk, SASB’s Oil and Gas – Exploration and Production standard recommends companies disclose the total fresh water withdrawn and percentage recycled, as well as that withdrawn from regions with High or Extremely High Baseline Water Stress. According to SASB’s analysis of company regulatory filings in its Annual State of Disclosure Report, 90% of the companies analysed mention water management as a risk factor, but only 30% include the use of metrics. As such, SASB’s standard can help investors understand which producers are betting big in water-stressed regions, and of those, which are well equipped to use the limited water resources more efficiently than their competition.

With domestic oil and gas activity ramping up and investors once again looking to pick potential winners and losers, an eye toward water risk may be a key element in ensuring profit projections don’t run dry.

David Parham is SASB’s Non-Renewable Resources sector analyst.